Norway's Progressive Prison System: A Model for Effective Rehabilitation and Reduced Recidivism Rates

October 15, 2024

Norway's successful prison system focuses on rehabilitation, with small facilities near inmates' homes, frequent visits, and emphasis on education and counseling. This approach has led to a significant drop in recidivism rates.

Some of the most sophisticated societies have understood that it does not serve their best interest to have a sizable portion of their populations languishing in prisons when they could be productive contributors to society.

In this regard, Norway’s prison system has been repeatedly showcased as a success story for tackling the problem of recidivism and addressing the rehabilitation of former convicts.

Like Barbados, Norway had a recidivism rate in the 1990s of around 70 per cent, and convicted persons were often back in the prison system within two years of their release.

Ironically, this publication reported in 2019 that 68 per cent of prisoners in Barbados found themselves in conflict with the law and returned to Dodds Prison shortly after release.

In essence, the thing that was meant to turn them away from a life of crime was simply recycling offenders and not rehabilitating them.

What has Norway accomplished that makes it the model for human rights advocates? Its system was transformed from prisons plagued by riots, assaults and escapes to a decentralised system of small prison facilities with fewer inmates who are imprisoned near where they lived, and up to three visits per week were encouraged for prisoners. Single prison cells are also not uncommon.

Prisons offer school, workshops, recreational activities, and anti-violence and drug counselling as the emphasis is on rehabilitation.

Important also in the Norway experience are the significantly reduced prison terms imposed by judges, with 90 per cent of sentences less than one year.

The result has been a massive drop in the recidivism rate of 25 per cent after five years, a greatly reduced prison population and slashes to the cost of incarceration.

There are also some examples such as the United States which we do not recommend to local authorities. The prison industrial complex, as it has been termed, involves the insidious practice of some industries and sectors that boost their corporate profits on the back of free prison labour.

It, therefore, is not in the interest of those enterprises to have low prison populations.

It is not expected that Barbados has the financial capacity to adopt wholesale Norway’s approach; however, a critical question remains. Can Barbados afford to continue Dodds’ revolving door for criminals or to have almost 70 per cent of incarcerated persons returning to the penal institution within 24 months of release?

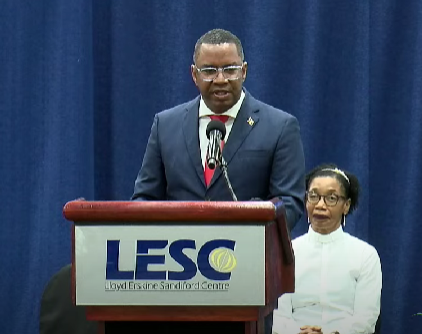

This situation is problematic on several fronts for the long-term advancement of the country. The announcement over the weekend by Home Affairs Minister Wilfred Abrahams that a parole system was “at an advanced stage” was an important development.

Addressing the Barbados Prison Service’s 167th-anniversary service, the minister noted the parole system would target inmates who had made strides in the rehabilitation process.

“If someone has been a model prisoner, there is no longer any practical reason for keeping them there,” he outlined. “Your debt to society has been fulfilled and you could probably be of better use outside where we can monitor you. We will still retain some element of control, but we won’t delay you in getting back to normal life.”

While there are some serious criminal offenders from whom society needs to be protected, there are others who deserve a second chance.

Mr Abrahams and the prison administration believe that prisoners who have acquired new, useful skills and qualifications should not be kept locked away if they have truly reformed and “can contribute positively to society”.

It must be acknowledged that even with strong rehabilitative programmes, a parole system, and other initiatives, there must be equal attention placed on public acceptance and education.

If society still holds fast to the belief that once a prisoner, always a prisoner, and job opportunities disappear with the slightest blemish on a police certificate of character, then ex-prisoners are likely to continue facing the obstacles that create the conditions for the return to a life of crime.

Society must be groomed to be more accepting of those who truly wish to turn away from criminal activity and to be positive contributors to the society from which they came.