Concerns raised over Barbadian education system's performance in recent exams

August 31, 2024

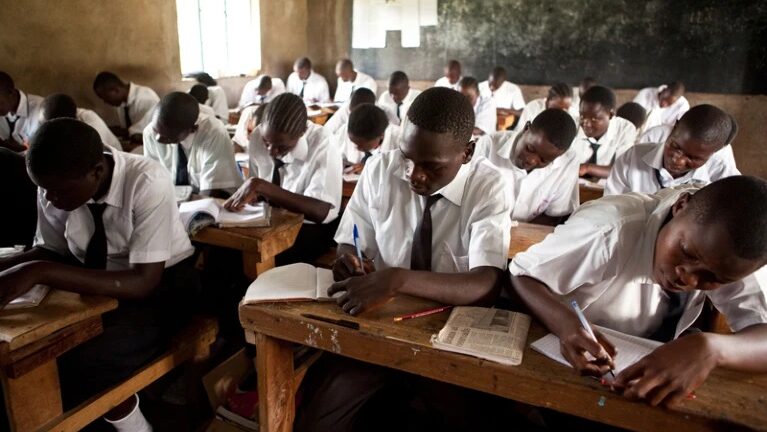

The Barbadian education system faces concerns over performance in primary and secondary levels, with declining pass rates in Mathematics and English reported by CXC for 2024 exams.

The recently published results in the BSSEE, followed by the performance data in the CSEC examination have raised concerns about the performance of the Barbadian education system, at least at the primary and secondary levels.

The results on the whole were not poor, at least not significantly much poorer than in recent years. For example, at the General/Technical Proficiency level, the CXC results in Mathematics for academic 1999/2000 was 63.67 per cent and for 2000/2001 it was a mere 49.65 percent. The results in English A were 67.50 in 1999/2000 and 75.85 in 2000/2001 (See ‘Digest of Educational Statistics. 1992-2002. pp.28-29) These are Barbados not regional figures. However, they raise serious concerns about our children’s capacity to satisfactorily master fundamental literacy and numeracy skills.

This year 2024, The Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) reported that there was a decline in the pass rate for Mathematics and English for the May/June 2024 exams across the region. More than 10,000 students, it posited, failed to achieve basic literacy and numeracy passing grades. It is also stated that ‘several students also received poor results in Chemistry, French, Spanish, Integrated Science, Information Technology and Principles of Accounts.’

Speaking in Dominica on Tuesday August 20, CXC’s chief executive officer Dr Wayne Wesley observed that, ‘we are losing almost 11,500 students every year who will not fully matriculate into university because of deficiencies in Mathematics and English.’ Dr Wesley concluded that ‘the lack of proficiency in these core subjects is not just an academic issue, but one that could have long-term socio-economic consequences.’

Following the publication of the results of the May 7 Common Entrance Exam, Minister of Education Ms Kay Mc Conney lamented that for the last ten years almost half of those taking maths had failed.

In this essay I will attempt to show that these deficits are not peculiar to Barbados and the region but are evident even in more developed western societies. However, the results at Common Entrance and CSEC raise doubt about the lie to the idea that the Education Sector Enhancement Programme more commonly known as Edutech would create ‘a learning revolution.’ I am still in possession of two copies of that document. The first time I read it I asked myself what precisely would constitute ‘a learning revolution.’ Learning would imply gains in children’s cognitive capacity in all aspects of cognition, accumulation of knowledge, comprehension, critical thought and clarity of expression.

It must also imply gains at the affective level, that school will be able to fashion character in relation to enhancing the values, attitudes and sensibilities of children so that they become good adults and in so doing improve society as a whole. The implication as stated implied that not only would these gains be made, but that they would be ‘revolutionary’ that is that they would occur in an appreciably short space of time, ‘revolutionary’ rather than ‘evolutionary.’

The Literature on Education at least what I have read, suggests that education reform strategies should begin to bear fruit in about eight to ten years. It is now 2024 and few would claim that either on the cognitive or affective levels the Barbadian education system has shown revolutionary change. In the affective domain we are witnessing a growing array of social pathologies that threaten to overwhelm us, including drug use, violence, young women going missing and rampant gun crime.

Most documents on education reform whether here or abroad are more political than pedagogical statements. The Republican administration of Geoge W Bush, (Bush 43) promised that ‘no child will be left behind,’ but successive Republican governments in the United States have refused to extend social provision for the poor. The Republican Party in the United States has opposed the Affordable Care Act(Obama Care) and even of late refused to support Biden’s Child Care Act which was on track to lift 24 per cent of American children out of poverty. The truth is that we can only accelerate education if we advance children socially and economically. The notion of affording every child a bright future is only achievable if we can substantively improve the socio-economic conditions in which children actually live.

In all the talk about transformation, a number of fault lines are showing up in Barbadian society and many are putting our children at increasing risk.

A special report in the Economist Magazine of July 13 is entitled Schooling Stagnation. Correspondent Mark Johnson writes: ‘Schools in rich countries are making poor progress. They should get back to basics.’ He posits that according to the Nation Assessment of Educational Progress in the United States, known as ‘The National Report Card, that ‘after years of progress, in the 2010’s education performance plateaued and after 2020 test scores started edging downward. The world’s leading reporter on education, The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) argues that after 1920 students even in wealthy countries were proving less competent in maths, reading and science. The exception were ‘the rising stars’ in Asia in contrast with western systems that are making little headway or in some cases are in perilous decline.’

A number of factors have been blamed for failing performance across the board. One such is the COVID pandemic which is obviously a cause. Many children for one reason or another missed out on instruction and a number never returned to school after the pandemic was over. The figures for Britain are shocking, particularly as it affected white working class boys. However, several reports consistently make the point that the decline actually predates the pandemic. A body of research points to growing rates of anxiety and other mental health issues plaguing today’s young people. According to the OECD, in 2022 about 18 per cent of teenagers rated their life satisfaction at four or less out of ten. This was up from 11 per cent back in 2015. This has been attributed to the onslaught of the pandemic and the negative effects of social media.

One other factor is the increasing use of cell phones and their presence in the classrooms. This is proving a serious distraction for students and teachers. Except for two provinces, the provincial governments in Canada have very recently banned cell phones in schools. The big question raised on CBC Canada’s programme The National (Tuesday August 27 2024) was how do schools effectively police the ban. The new technology is proving an increasing deterrent to quality reading. More than 60 per cent of rich-world pupils say that their phones or tablets distract them during school lessons. Students who reported spending a lot of time fiddling with devices in school score lower than others in international test.

Another factor is the changing nature of children, schools and society. Classrooms have become more disruptive. Today ‘s children are generally less deferential to adults, including parents and teachers who in a more liberal climate have less recourse to the disciplinary stricture they once had. The homes are increasingly less supportive of the school as it struggles to cope with the problems coming from the said homes and the society at large. According to the Economist magazine of July 13, 2024, in England 80 per cent of primary schools polled before the pandemic said that they were devoting more time to social and emotional education than five years previously.

Finally it is becoming increasingly clear that the teaching profession is finding it difficult to co-opt and retain the kind of teachers needed to promote the kind of changes that educational systems say they want to effect. That is the subject for another article.