Analysis of World Bank Presentation on Taxing Wealth for Equity and Growth: Implications for Caribbean Countries

October 13, 2024

This article critiques the World Bank's focus on taxing wealth for equity and growth in Latin America, neglecting the Caribbean's unique challenges and advocating for essential measures like debt relief and vulnerability index adoption.

On Tuesday, October 8, I went to a meeting at the World Bank and listened with growing disappointment to a presentation on Taxing Wealth for Equity and Growth, supposedly focused on Latin America and the Caribbean region.

I was less disappointed about the lack of attention on the Caribbean and the focus on Latin America. With great unhappiness, I have come to expect this distortion from all global financial institutions. It seems that the Caribbean is too small to matter, except when strictures have to be placed on initiatives for achieving social stability through financial measures. But as the representative of a Caribbean government (Antigua and Barbuda) and as a regionalist, sensitive to the implications for every Caribbean Community (CARICOM) country on the situation of all others, I was more disturbed about the paucity of data presented about Caribbean countries and the lack of any analysis on the sub-region.

Neither the October 8 presentation nor the full report released on October 9 provided any reason for optimism that the World Bank is addressing the real challenges of promoting equity and growth in the Caribbean. The report, a precursor to discussions at the bank’s upcoming annual meeting, focused solely on taxing wealth for equity and growth and ignored the measures CARICOM states have long advocated as essential to achieving these goals.

The report fails to mention critical measures, such as: adopting the multidimensional vulnerability index as a criterion for concessional financing—a proposal actively advocated by small island developing states (SIDS) and CARICOM at various global forums but not yet fully integrated into global financial policies. Additionally, debt relief, through mechanisms such as forgiveness and restructuring, remains a critical issue for the region. While some debt relief efforts, like the IMF’s Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) and the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), have helped developing nations during crises, these programs primarily benefited low-income countries outside the Caribbean. Caribbean nations continue to struggle with high debt burdens and need more targeted solutions from international financial institutions.

The report also overlooks the urgent need for improved recovery windows for climate-related disasters. Despite irrefutable evidence of accelerating climate change, including projections that the world is on track to exceed the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold within the next decade, financial responses for vulnerable Caribbean nations remain inadequate. The Caribbean’s vulnerability to extreme weather events, exacerbated by climate change, makes the lack of focused attention on these issues especially concerning.

The report highlights two potential wealth tax sources. The first, championed by the leaders of Brazil and France, proposes a two per cent levy on the world’s 3 000 wealthiest billionaires. However, as of 2024, Latin America and the Caribbean together have only 153 billionaires, with Brazil alone accounting for 68, and Mexico for 20. CARICOM countries likely have very few billionaires—if any—with most wealth in the region concentrated in larger Latin American economies. For instance, Carlos Slim of Mexico, with a fortune of $102 billion, and Eduardo Saverin of Brazil, with $28 billion, dominate the region’s billionaire rankings. A two per cent tax on such a small number of individuals would barely generate significant revenue, especially for smaller Caribbean countries. In small nations like Antigua and Barbuda, where there may be dozens of millionaires, it is unlikely that any billionaires exist.

Moreover, as the report itself notes, taxing liquid assets is particularly challenging in countries with weak enforcement, where wealth can be easily moved offshore, a concern highlighted by the UNDP during its examination of wealth trends in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The report then shifts its focus to taxing property, claiming that it is “a relatively fixed and easily identifiable asset” and thus less prone to evasion. While this may be true, the Bank’s statement reveals a disconnection from the historical, social, and cultural realities of Caribbean societies. A legacy of slavery, indentured labour and worker exploitation left the majority of people in the sub-region with little or no property, though owning “a piece of the rock” and a home remains a deeply ingrained aspiration. Since gaining independence, CARICOM governments have made it a priority to encourage land and home ownership. Increasing property taxes now would undermine this policy, potentially stripping many persons of the very properties they worked so hard to acquire.

The report notes that the low contribution of property taxes to total tax revenues in Latin America and the Caribbean (two per cent) stems from outdated and inaccurate property valuations, often far below market value. While this broad statement may not fully reflect the Caribbean’s reality, it does raise an important point: improving property valuations and tax collection systems should be examined across the region.

Alarmingly, the report asserts that the Latin American and Caribbean region is “close to vanquishing inflation” and that lower interest rates will ease the stress on households and banking sectors, potentially spurring economic growth. While this may hold true for some Latin American countries, such as Brazil and Peru, it overlooks the unique causes of inflation in Caribbean nations. Most Caribbean inflation is imported from the region’s largest trading partner, the United States, where competitive, subsidised agricultural production contrasts sharply with the high costs of small-scale farming in the Caribbean, including rising input costs.

Furthermore, Caribbean countries, excluded from concessional financing from institutions like the World Bank, are forced to borrow on the international commercial market, where interest rates remain high. Although competition among banks and credit unions in the region has led to recent reductions in interest rates, government borrowing from local banks risks crowding out private sector investment.

The World Bank’s report is useful in acknowledging that “progress on poverty and inequality remains slow” in Latin America and the Caribbean. This growing issue lies at the heart of tensions within and between states, particularly in smaller economies like those in the Caribbean, which are often overlooked in global financial discussions. It is something to which the World Bank should formulate focused solutions.

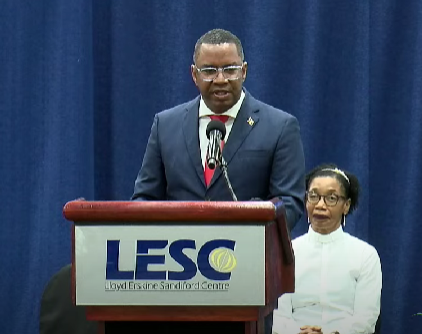

Sir Ronald Sander is Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the US and the OAS. The views expressed are entirely his own.