British Monarchy Comments on Reparations in Commonwealth Summit: Insights and Stances

October 26, 2024

King Charles III acknowledges past injustices at Commonwealth summit. UK government stance unclear on reparations for transatlantic slave trade. PM Starmer prioritizes climate change over reparations discussions.

“None of us can change the past, but we can commit with all our hearts to learning its lessons and to finding creative ways to right the inequalities that endure.”

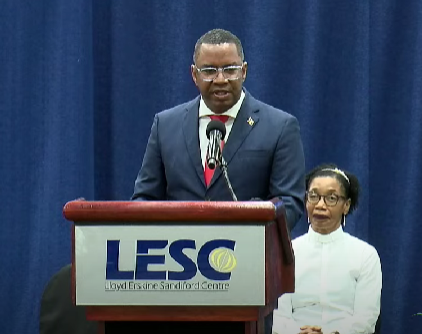

Those were the comments of King Charles III, the head of the British monarchy, on Friday as he addressed the Commonwealth summit in Samoa. It remains unclear whether this is a coordinated British government stance on reparations, but it surely seems that way.

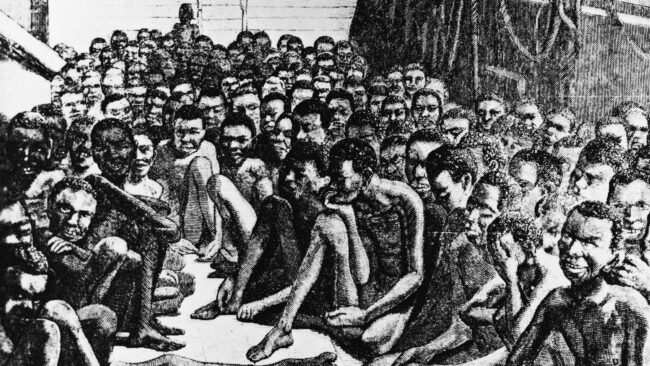

Just 24 hours earlier, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, made it clear to the BBC that the United Kingdom was “not going to be paying out” reparations for the transatlantic slave trade, in which untold numbers perished on slave ships and in the Atlantic Ocean, while millions of survivors were condemned to lives of dehumanising slavery on sugar plantations across the Caribbean and the Americas.

Reeves said she understood why Commonwealth leaders, most of whom represent former slave colonies, would make such demands. However, she emphasised that it was not something the British government would commit to.

Meanwhile, the British Prime Minister, Sir Keir Starmer, was outlining his priorities at the Commonwealth discussions, and reparations did not feature among them. Starmer preferred to focus on what he termed “sexier topics” like the challenges of climate change rather than on the years of exploitation of black Africans and their descendants, whose labour helped to establish the British Empire as one of the most powerful in modern history, or the enduring effects of slavery and racism that still impact people across the Commonwealth.

“That’s where I’m going to put my focus – rather than what will end up being very, very long endless discussions about reparations,” he was reported as saying.

Without a tinge of sympathy, empathy, or consideration for the sensitivities of the Commonwealth’s majority member countries and their representatives, the British Prime Minister drove his point further: “Of course, slavery is abhorrent to everybody; the trade and the practice, there’s no question about that. But I think from my point of view… I’d rather roll up my sleeves and work… on the current future-facing challenges.”

Whether Starmer is shamelessly insensitive or completely ignorant, his comments on the issue are worthy of condemnation. The outright rejection of legitimate claims for reparations led by the Caribbean Community, without so much as an apology, is a slap in the face for Britain’s former colonies.

The remarks of King Charles III, the British Prime Minister, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer appear to be choreographed, perhaps aimed at quelling the growing calls for reparatory justice.

Once viewed as an outlandish demand, restitution for the violent exploitation of Caribbean ancestors is increasingly recognised as a legitimate issue. The remnants of the racism that fuelled the slave trade cannot simply be dismissed.

As social historian Verene Shepherd, Director of the Centre for Reparation Research at the University of the West Indies, Mona, outlined in an article for the UNESCO Courier, there remains a lack of awareness of the “enduring financial implications for the enslaving societies as well as for the slaves and their descendants.”

Shepherd writes: “Governments and institutions that benefited from the conquest, chattel enslavement, and colonialism are being demanded to acknowledge the role they played in these systems, and to make adequate restitution.” She adds, “The key demand is for these entities to recognise that their wealth was created from the destruction of countless racial and ethnic communities, cultures and societies, which continue to have far-reaching implications on their ability to thrive.”

A critical question remains: Are Caribbean countries too consumed with managing struggling economies to devote the necessary time and resources to bring this battle to its logical conclusion?

Other groups, such as the Jews and, ironically, the former slave owners, have benefited from reparations. Why, then, is it so difficult for Britain and other European colonisers to accept that reparatory justice must be extended to the descendants of African slaves, whose forced labour built empires from which the industrial powers still profit?